I’m six years old when my Dad sits me on his lap in his home office, and shows me the screen of his computer. It’s a Sharp MZ80B, with brightly-colored, extremely clicky function keys, and the earth is spinning on its built-in green-screen display. Push the space-bar, and the earth spins twice as fast.

My childhood mind is blown.

Sometime later, my sister and I are running around in that same home office. There are large boxes, either wood or some kind of very tough cardboard–and they’re actually sensors. Those sensors are detecting the plastic tags we’re wearing, ones that will later be used by the software my Dad is writing to identify individual cows, and from that, where they stand in the herd’s hierarchy.

We, of course, understand none of that. We run around, moo, and interact with the box to make sure that it’s correctly identifying the animals. (There’s a whole other story about this that Dad told me later, one about what can happens when you initialize your boolean variables incorrectly, and a lesson about not testing your code in production–but for today, this is enough.)

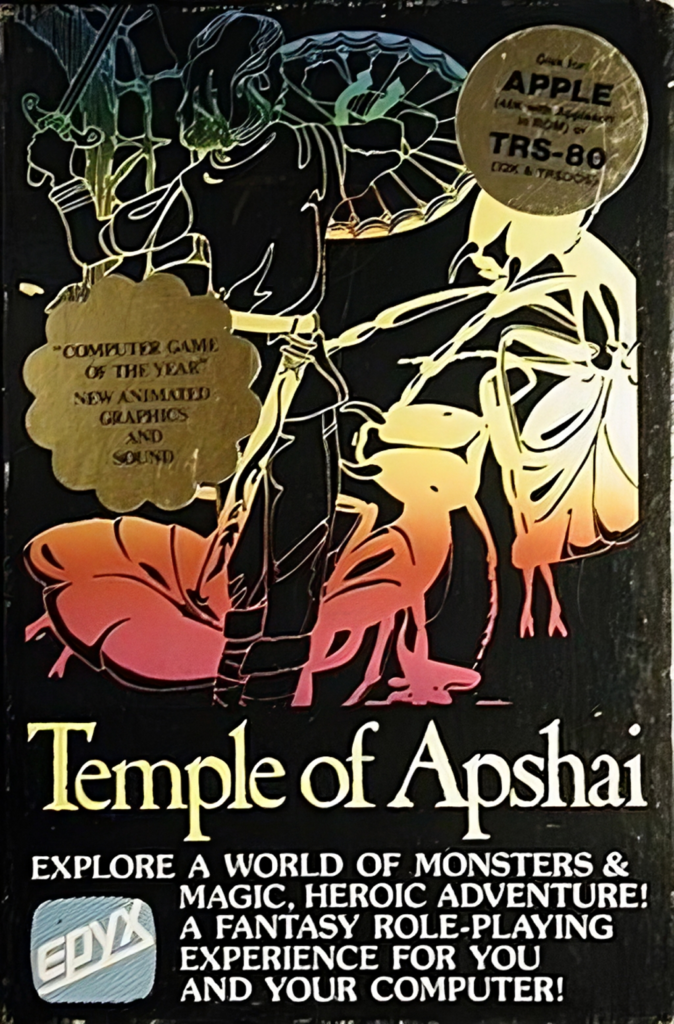

But the main point about all this is, computers have always been around us in our house. Before the Sharp, there had been others, some that pre-date me, at least one that Dad built himself from a kit, and another mystery system that ran this game:

One of the earlier dungeon adventure games, unlike the genre of roguelikes, Apshai’s dungeons were fixed rather than being procedurally generated, and the manual that came with the game included descriptions of the rooms that you encountered. These were critical to the experience, and included key information, but they were far too much to include in the game’s code itself back then.

(My Dad mentioned playing this game in a house that pins the time window down to sometime between 1979 and 1982, adventuring under the name of “Cornytoes the Cack-Handed” — but the game was popular enough, and adapted enough, that this really doesn’t pin the system down.)

I never understood when I was younger that my Dad had programmed as a side hustle, writing software for electronic transformer design, and for the automated feeding of cows. That software paid for our first family car–but I never knew that, I only knew of his day job as an electronic engineer. And I somehow became a career software engineer myself before we ever talked about it.

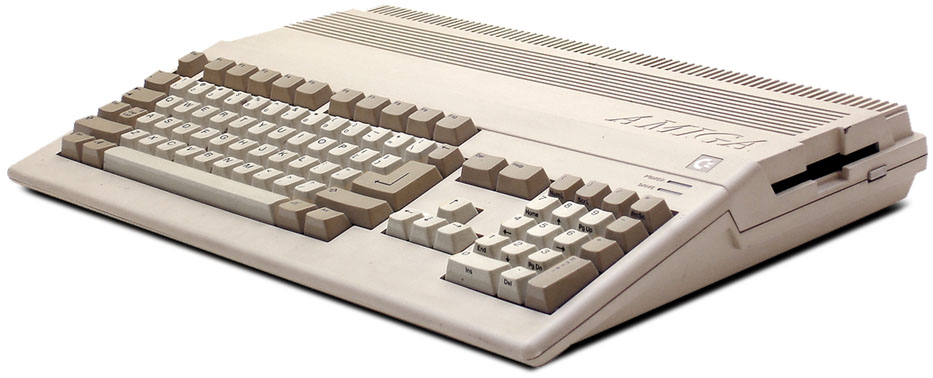

But I’d always learned about programming from my Dad. After we upgraded to the Amstrad PC 1640DD (pictured above), to which he added a mighty 40MB hard disk–serious tech at the time, which required you to manually park the disk before shut-down–he began playing in QuickBASIC. He made a procedurally generated maze game that rendered in mock-3D, similar to Pool of Radiance. Another time, he wrote a program to analyze trends and predict score draws for the British football pools.

(The first time he tested it, it nailed the results, but he’d put no money down that week. Of course, it never ever managed to repeat that success again.)

I was fascinated, but didn’t really understand much of it at first, and it would take years before I really did. I played around with coding stupid things on the Sinclair Spectrum +2 (the first computer in our house that was for my sister and I, rather than one to be shared), sometimes typing out code snippets I didn’t understand from one of the Sinclair magazines of the day, or later working to create a sprite you could control with joystick input. Like most things at the time, I was very quick to be excited by some other new idea I had, and move onto that instead.

Later, as a teenager, I fell in love with the Commodore Amiga. I played a procedurally-generated dungeon crawler game on it, called Moria, which reminded my Dad of Temple of Apshai back in the day. And I got into trying to write text adventures, using a language called AMOS, which was not really intended for that sort of game writing at all.

But it was working on those text adventures, solving the problems of implementing a parser, tracking world state, and running into memory limits for the first time thanks to my over-ambitious game map, that turned me away from astrophysics (the academic path I’d expected to follow) and onto the path of computer science instead. It became my bread and butter–and as much as I do sometimes miss the astrophysics I chose not to pursue, I know I was lucky to find a career I love.

But none of that would have happened without my Dad having loved it first. He planted those seeds of curiosity, both by his playing around with it, and by his own general enthusiasm for computers and advancing technology.

Miss you, Dad.